As Pope at the head of the Church, he occupied the chair of Peter from 678 to 681, in truth a brief period of time, but for us Croats it was of the utmost importance.

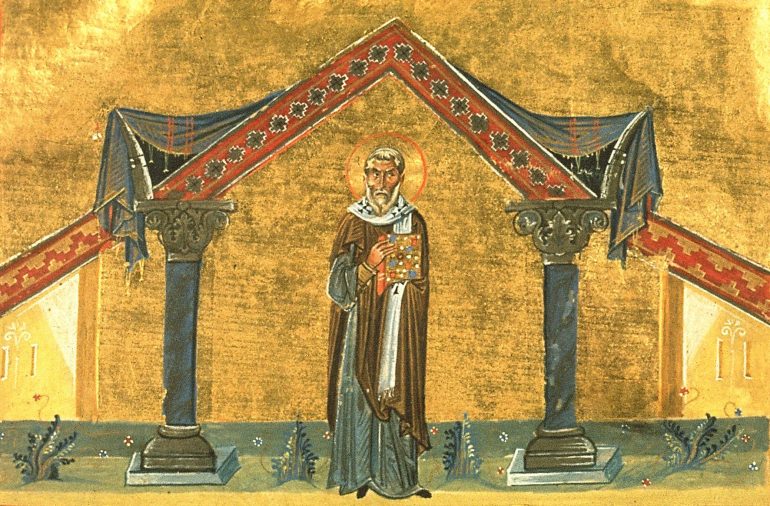

Although we know relatively little about Pope Agathon’s life, his name and memorial day should evoke a joyous memory in the heart of every Croatian believer. He stands as a bright figure at the dawn of our history that begins with the baptism of our people (who were the first of the Slavic people to become Christian). As Pope at the head of the Church, he occupied the chair of Peter from 678 to 681, in truth a brief period of time, but for us Croats it was of the utmost importance.

Pope Agathon was born in Palermo, Sicily. After 20 years of marriage, he became a widower and entered the community of Benedictines. After being appointed cardinal, he was elected Pope in 678. He occupied St. Peter’s chair for less than three years, but he conquered everything with his gentle and cheerful disposition. He convened a church council in Rome around Easter 680AD, from which he sent an epistle to Emperor Constantine IV in Constantinople. Along with the Pope, the epistle was signed by all 125 bishops present, including the bishop from Istria, while there were no signatories from the rest of the Croatian territory. The Pope’s letter reads, among other things: “Among the barbarian peoples, both the Lombards and the Slavs, also in the midst of the Franks and Gauls, are many of my servants (ie bishops), who, in view of the apostolic faith, do not cease to labour zealously . . .”

Our historians Marković, Sakač and especially Mandić, confirm the fact that from this Pope’s letter it can be seen that in the year 680, bishops worked in the midst of some Slavic peoples and that this people had already accepted Christianity prior to that year. This people can only be Croatian, because other Slavic peoples were baptized only at the end of the 8th and the beginning of the 9th century, and according to Agathon’s epistle, as early as 680 there were several bishops already ministering among Croats, and Croats were Christians at that time.

In addition to that historical data, for us is even more important what the Byzantine emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, as a contemporary of the first Croatian King Tomislav (who reigned from 912 to 959) writes in his work “De administrando imperio”. He writes: “After their baptism, the Croats set up a treaty with their own hands and swore with a firm and unwavering faith to St. Peter that they would never invade other people’s lands or go to war there, but that they would rather live in peace with anyone who wanted to. And in return, they received from the Pope a prayer (a promise) that he would fight for them and that the God of the Croats would be at their aid whenever other nations invade the Croatian land and disturb them with war, and St. Peter, a disciple of Christ, will endow them with victory.”

In 1931, Jesuit Father Stjepan Krizin Sakač (1890-1973) wrote a notable and important treatise titled “Ugovor pape Agatona i Hrvata proti navalnom ratu (oko g. 679.)” (The non-aggression contract between Pope Agathon and the Croats circa 679AD), our first international peace treaty, which was once translated into Spanish and convincingly proves that this treaty would correspond to the truth, and the Pope, whom the Emperor does not name, would be none other than Pope Agathon.

This text, we would dare to say, enters into the sacred pages of our history and it would be worthwhile for us as Croats and as believers, to delve deeper into it more often. It speaks, as a matter of first priority, of a very significant event which stands at the beginning of all Christian nations, and that is our baptism. With this event, we entered the circle of “cultured” European nations with all the ensuing consequences, because as a nation we began to experience the Christian mystery, which dedicated its wealth to so many of our sons and daughters, and then built so many churches that became the most enduring and eloquent witnesses of our spiritual culture.

This text also speaks of our national connection with God and with Peter, a disciple of Christ. The Croats swore to St. Peter that they would not wage invading wars and would rather live in peace. History testifies to the extent they fulfilled that oath. As history is often biased, it is difficult to make an accurate judgement on the basis of all the written documents. They certainly closed the door to conquests with this oath, set it as an ideal, and we believe that they largely achieved it. Think of the beatitude that Jesus included in His sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God!” (Mt 5:9). That is why the Croats received the special protection of God, and through their truly difficult history, battered and suppressed from all sides in this windstorm, they still managed to survive as a nation until today.

The connection to St. Peter, the first pope, already at the beginning of our history, and the treaty with Pope Agathon, are probably the reasons that the Croats throughout their history remained faithful to the papacy and Rome, always resolutely rejecting temptation, whether schism, or heresy. And that, surely, was a great grace to our people and should be a sacred obligation for the future as well.

Pope Agathon also used his business skills when the English bishops turned to Rome for advice. It was when St. Wilfrid of York and St. Theodore of Canterbury addressed Rome to demarcate the dioceses. He returned the deposed Bishop Wilfrid to English York, and sent the Benedictine abbot, Archbishop John, to the British Isles, to teach the English Gregorian chant and thus expand the Roman liturgy.

The most important event of Agathon’s pontificate is the Sixth Ecumenical Council (also known as the Third Council of Constantinople), called the Council of Trullo. The Council was held from 680 to 681, but unfortunately the Pope did not see it through to the end. At that Council, a monotheistic heresy was condemned that claimed that there were two natures in Jesus, but only one will. Two of Agathon’s letters addressed to the Council were instrumental in the delivery of the outcome.

Pope Agathon died on January 10, 681, and his body rests in the church of St. Peter in Rome. Above his grave is a Latin inscription of a poem of 12 verses.

The name “Agathon” is of Greek origin and means “good”.

The original article in Croatian can be found here: Sveti Agaton, papa